This post first appeared in the Future Crunch newsletter, a weekly roundup of stories of progress for people and the planet. You can subscribe for free below.

A great darkness has settled on the land. As the plague enters its seventh season, a virulent new strain has emerged, threatening all our hard won gains. Once again our hospitals buckle under the pressure and the science of mask-wearing regresses into hapless debates about freedom. Once again our doctors and nurses are asked to do the impossible, despite having done it hundred times over. From Algeria to Mexico to Indonesia, the body counts rise and the curves bend in all the wrong directions. Charlatanism, conspiracy and political propaganda thrive, moving at light speed through the networks. Once again, our political leaders are exposed as utterly inadequate to the task at hand.

Catastrophe is in the air. Days ago, the largest peer-reviewed process of all time confirmed that we are in the midst of the greatest planetary crisis we’ve faced since we came down from the trees. July was the hottest month ever recorded; the Earth is hotter than it has been at any moment since the beginning of the last Ice Age. Heat waves settle across entire continents, floods rip through Germany, China and Japan, drought stalks Myanmar, Venezuela and Mali, wildfires explode across the Pacific Northwest, the Mediterranean and Siberia. Our scientists tell us humanity is unequivocally responsible for these events. “In the past, we’ve had to make that statement more hesitantly. Now it’s a statement of fact.”

The Arctic will be ice free soon and our grandchildren probably won’t see the coral reefs, and yet the few thousand bankers, industrialists and politicians responsible for this, the greatest of all crimes, simply switch from denial to delay, clutching their forty pieces of silver to the grave. Under smoke-red skies ageing billionaires ride metal phalluses into the heavens, with wrinkled lips and sneers of cold command. Back here on Planet Earth, tin pot tech emperors sell soma dreams of The Metaverse to the masses, while billions of their fellow human beings struggle to put food on the table.

In the graveyard of empires, 20 blood-soaked years of ‘nation building’ has unravelled in days. A sect of religious fanatics has swarmed back into power, overrunning the country with shocking swiftness and plunging millions of women and girls into a terrifying real life version of the Handmaid’s Tale. Democracy’s flame sputters out in the last remaining holdout from the Arab Spring, Nobel laureates wage war on their own citizens, and emboldened autocrats everywhere tighten their grip.

Pax Americana has never looked shakier. In Florida, the once and future King lurks, squamous in his gilded lair, leaching poison into the body politic. In the east, a new rival grinds Xinjiang and Hong Kong under its boot, and looks across the Taiwan Strait towards the last remaining isle of freedom. The networks of trade will be no match for the drumbeat of war, should it come. The markets will not help either. Animal spirits have taken hold of all but the most prudent of investors, regulators wrestle with the spectre of inflation, and the dream of home ownership disappears beyond the reach of an entire generation.

This story is the oldest one in the book, and we are all intimately familiar with its lurid details. It’s on the front page of every newspaper and at the top of all of our feeds. You can tune it out or turn it off, but you cannot ignore it.

It's the story of Collapse.

Here’s another story.

In the last month, over a billion COVID-19 vaccines have been administered around the world, more than 30 million a day. Almost a third of humanity has now been reached; by the end of this year we will have dosed half the people on earth: the single most extraordinary public health achievement in our species’ history. The vaccines are unbelievably effective. Less than 1 in 25,000 of fully vaccinated people exposed to the Delta variant have ended up in hospital, and only 1 in 100,000 have died. Global death rates are climbing among the unvaccinated, yes, but they’re still well below the highs of earlier this year. The pandemic isn’t over, but an end is firmly in sight.

In the process of containing the virus, Homo sapiens has figured out how to manipulate the basic machinery of life, tinkering with the flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to make proteins, the intricate nanomachines that perform most tasks in living things. This technology was still years, perhaps decades away from being approved, but thanks to the ultimate real world clinical trial it’s now as much as part of medicine as antibiotics or painkillers. Trials are already underway for mRNA vaccines for everything from cancer to malaria and HIV. Their impact will stretch far beyond this pandemic, potentially saving hundreds of millions of lives.

It’s not just the science that’s leapt forward a decade; the process knowledge for making, distributing and administering those vaccines at scale has accelerated. The labs, grow vats, glass vial factories, warehouses, trucks, refrigerators, forms in triplicate, computer systems, training manuals and hard-earned know-how will be with us long after the COVID-19 headlines are gone, a public health legacy felt for generations to come. In the background, another medical revolution is brewing in the form of psychedelic therapies, which stand poised to transform mental health as decisively as vaccines once transformed infectious disease.

That IPCC report makes grim reading yes, but there are also reasons for hope. A decade ago the world was on track for a particularly terrifying climate future. China was building a new coal plant every three days and global emissions were increasing at a rate of 3% per year. Ten years later, we’re in a very different place. Clean energy is now definitively cheaper than dirty energy, making climate change a solvable problem by expanding the universe of the possible. In the past, nations faced an impossible trade off between climate disaster or material impoverishment. Today, thanks to the efforts of scientists, engineers and entrepreneurs, that trade off no longer exists.

We’ve begun fixing the problem. The world has produced more electricity from clean energy — solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear — than from coal in the past two years. 32 countries have absolutely decoupled their emissions from economic growth, and global emissions will start falling this decade as the energy revolution takes hold. Is it enough? Not yet, but the darkest climate futures of a decade ago are no longer in play. With continued effort it’s possible to lower the curves even more. It will take heroic effort, unprecedented cooperation and visionary commitment. It will mean making profound changes in our societies, economies, our ways of doing things. The good news? We know how to do it.

From India, come reports that wind and solar capacity have passed the historic milestone of 100GW, even as no new coal plants were switched on in the first quarter of this year. Coal pipelines have collapsed in Turkey and the Philippines, Sri Lanka just ruled out any new plants, and in South Africa, the state utility says it is now “virtually impossible” to get finance for its coal projects. In the United States, the EIA has released data showing that the number of producing coal mines declined by 18% last year.

Slowly but surely, the not-so-invisible hand of the market is starting to bite. A new analysis just revealed that the UK’s low carbon economy is now worth £200bn, four times the size of the country’s manufacturing sector. More than 75,000 businesses, from wind turbine manufacturers to recycling plants, now employ more than 1.2 million people in Britain’s green economy — a fact not lost on its vote-grubbing politicians. In Europe, the average cost of electricity from renewables is now half the price of fossil fuels, two thirds of the continent’s electricity is generated from zero carbon sources, and coal generation is 16% lower than this time two years ago.

Climate tech investments are smashing all previous records. Three weeks ago, two global asset managers, TPG and Brookfield, closed a combined $12.4 billion in climate investment funds. That’s more money committed in a day than used to be raised in years. Mercedes just became the latest car brand to announce it’s going all-electric by 2030. In Alaska, a federal judge just blocked a massive new oil drilling project, citing climate concerns, and Greenland just banned all oil exploration, despite being home to billions of untapped barrels. In Sweden, the first delivery of green steel made without coal has been made and Baowu, the world’s largest steelmaker, fired up its first large scale hydrogen-based forge two weeks ago, and good luck finding a news story anywhere about that.

After forty years of trickle up economics, the pendulum is swinging back in favour of fairness. In the United States a combination of stimulus checks, food stamps, unemployment benefits and child tax credits has reduced the number of Americans living in poverty by nearly half this year. That’s the largest short-term poverty reduction in the country’s history, a 45% decline from 2018. Two bills are currently working their way through Congress right now, the biggest investments in remaking the economy, rebuilding infrastructure and expanding the social safety net since the New Deal, and the most significant action to confront climate change in US history.

In the Himalayas, India and China have completed troop disengagement from the Gogra area of eastern Ladakh as part of an agreement reached during their latest round of military talks. In Rwanda, the health ministry says it has made astonishing progress on combating viral hepatitis, and in Mozambique, hundreds of thousands of people just gained access to clean water and electricity following the completion of a project in the central province of Manica. In the DRC, tens of thousands of former child miners are now attending school, two years after the government made primary education free for all.

Iraq has just reclaimed 17,000 looted artifacts in its biggest-ever repatriation, in Mexico, women have made historic gains in recent elections and in Argentina, the government just guaranteed the right to gender identity for people who don’t recognize themselves as either female or male. Three weeks ago, Sierra Leone’s parliament voted unanimously to repeal the death penalty, making it the 23rd African country to prohibit capital punishment. “This vote is a major victory for all those who tirelessly campaigned to consign this cruel punishment to history and a strengthening of the protection of the right to life.”

In Indonesia, one of the world’s biggest palm oil growers has announced a plan to rehabilitate an area half the size of New York to atone for its past clearing of rainforests and peatlands. In Bolivia, a massive new two million acre reserve has been established on the Amazon’s deforestation frontier, thanks to a partnership between indigenous communities and private donors. Last month, the United States restored protections for the Tongass National Forest in Alaska, the largest intact temperate rainforest in the world, home to thousands of watersheds and fjords, and more than a thousand forested islands. The new protections will end large-scale old growth logging and support restoration, climate resilience, and recreation.

Not to be outdone, Canada has announced major new conservation funding for its Prairie provinces, conserving up to 30,000 ha of wetlands, grasslands, and riparian areas, on top of restoring 6,000 ha and enhancing another 18,000 ha. At the beginning of this month, the World Heritage Committee removed the Salonga National Park, Africa’s largest protected rainforest and home to 40% of the Earth’s bonobo apes, from its list of threatened sites. A fortnight ago, Thailand banned sunscreens containing the chemicals that damage coral from all of its marine national parks, and France joined Germany in outlawing the culling of male chicks.

India’s government recently re-affirmed its commitment to banning all single use plastic next year, and Target, one of the world’s largest retailers, just committed to a 20% cut in virgin plastic by 2025, joining Walmart, Coca-Cola and Mattel, who have made similar commitments in the last year. From picturesque Mediterranean isles to New York’s bustling harbor, oyster colonies are depolluting the sea, and off the coast of Scotland there are four no-take zones now and climbing, as the idea spreads further afield. Across vineyards and olive groves in Spain, a new regenerative agriculture model is taking hold, allowing grass and wild flowers to flourish between the trees. In Beirut, they’re up-cycling rubble from last year’s explosion into public amenities like sidewalk pavement, trash bins and benches.

Off the west coast of the United States, orca whales just received new protections, expanding their critical habitat from the Canadian border down to Point Sur in California, an additional 41,206 km² of foraging areas, river mouths and migratory pathways. Further north, recent sightings of the North Pacific right whale offer hope that one of the rarest of the large whales may finally, be starting to recover. In Spain conservationists are reporting there are now 1,100 Iberian lynx in the wild, thanks to one of the most successful reintroduction programmes of all time, and from Nepal, comes new data showing the number of tigers in the country has almost doubled in the past ten years.

This is the story of Renewal

We’re not sharing it to balance some kind of imaginary scale, or look on a bright side that doesn’t exist. We’re living through a pandemic that continues to cause untold suffering, our climate future is still genuinely scary, and it’s impossible to imagine the fear and anguish of millions of people in Afghanistan right now. Instead, we want to remind you that even during the darkest of times, there is always another set of stories out there. You won’t find them on the front pages of the New York Times and you definitely won’t get them from your Apple News feed, but they’re all true, and they’ve all happened in the last month too.

As Jane Goodall says:

These are stories that should have equal time, because they’re what gives people hope.

Kurt Vonnegut, the great observer of the horrors and ironies of 20th-century civilization, once said that his ‘prettiest’ contribution to culture wasn’t his novels, but his Master’s thesis in anthropology for the University of Chicago. His idea, which was rejected because “it was too simple and looked like too much fun” was that stories have shapes, and that the shape of any given civilization’s stories are as interesting as the shape of its arrowheads or pottery.

To illustrate his point, Vonnegut plotted the story of Cinderella on a graph, charting misery versus ecstasy over time. The arrival of the fairy godmother kicks off a step by step climb in fortune, leading to a high point at the ball, followed by a sudden reversal at the stroke of midnight. The good times come roaring back though, thanks to that glass slipper, leaving our protagonist even better off than she was before. This arc, said Vonnegut, is evident in some of our favourite stories, from the New Testament to Jane Eyre and Frozen. It’s immensely satisfying, hence its enduring appeal.

There are other story arcs too. In Rags to Riches, a continuous upward climb towards happily ever after (and in Riches to Rags, the opposite). In Man in a Hole, the main character gets into trouble, then gets out of it again (Alice in Wonderland, Finding Nemo), or even better, double Man in a Hole, for double the emotional impact (hello Harry Potter and The Lion King). In Icarus, there’s a rise, followed by a fall (Jurassic Park, The Great Gatsby, actually pretty much anything with the word ‘great’ in its title), while Oedipus is the tragic mirror image of Cinderella giving us Frankenstein, Moby Dick, and The Godfather.

The shapes are different, but the dramatic mechanism is always the same: a change over time, moving between good and ill fortune. This up and down motion reveals a deeper meaning, hints at an underlying pattern, gives us a moral code to make sense of the chaos of real life, or perhaps just an emotionally satisfying ride. Put simply, stories have to narrate change. If there is no rise or fall it isn’t a story. It’s a series of events.

Our story arcs are a legacy from the Greeks, who gave us tragedy, a genre built on rises and falls that peak with a climax. Aristotle called the moment of maximum intensity peripeteia — which translates to reversal — and named the aftermath catharsis, the release of emotional energy. That’s how we all know pride comes before fall and that the darkest hour is always before the dawn. It’s why Frodo and Sam save The Shire and sail off into the sunset, and why Dorothy returns to Kansas, forever changed, yet still insisting “there’s no place like home.”

Story arcs also show up in our history. Ever noticed how different time periods always seem to alternate between collapse and renewal? The ‘Dark Ages’ comes after the sacking of Rome, followed by some medieval mud and blood but then from out the darkness, hallelujah! Renaissance and Enlightenment! It’s worth pointing out that the women and men who lived during the thousand years before the arrival of the Ninja Turtles were not conscious of living in the Middle Ages, nor were the alchemists dicking around with heavy metals aware they were in the midst of a scientific revolution.

The labels we give to the past aren’t descriptors. They’re propaganda. They depend on who’s telling the story, and are applied post facto, usually for political purposes. Remember — when Europe’s peasants were supposedly grubbing around in the dirt, the Ming Dynasty was building The Great Wall and creating encyclopedias. The words we give to things are powerful. That’s how the genocide of an entire people becomes a country’s glorious founding myth, and why making something great again is always a good marketing strategy.

Look, we get it. We also want to make sense of this moment in time. We want the waveform to collapse, and for the world to resolve itself into clear focus, telling us where we are in the grand narrative of human history. Are we on the way up, or on the way down? After 18 months of this craziness we’re all starving for narrative certainty. Are all those awful stories of Collapse the harbinger of something even worse, or are they the dark before Renewal’s new dawn? The truth is that we do not, and cannot know.

Real life is not a story, and history isn’t a moral arc

Perhaps there’s a better way of thinking about Collapse and Renewal. Instead of expecting them to follow each other in sequence, like they do in our stories, what if we consider them as things that happen in parallel? In making sense of the world, what if we give up trying to figure out whether we’re in the upswing or the downswing of history and instead, make peace with the idea that we’re in the middle of both — the long-awaited fall from grace and the journey to the promised land.

This idea, of a ‘Great Turning’ existing side by side with a great collapse, is one we first came across in the work of ecological philosopher, Joanna Macy, and it’s become one of the cornerstones of our worldview. It accepts that the signals for disaster are everywhere we look, and so are endless examples of human progress, environmental stewardship, ecological restoration and extraordinary acts of kindness, all densely entwined and far too complex to resolve into a simple three act structure.

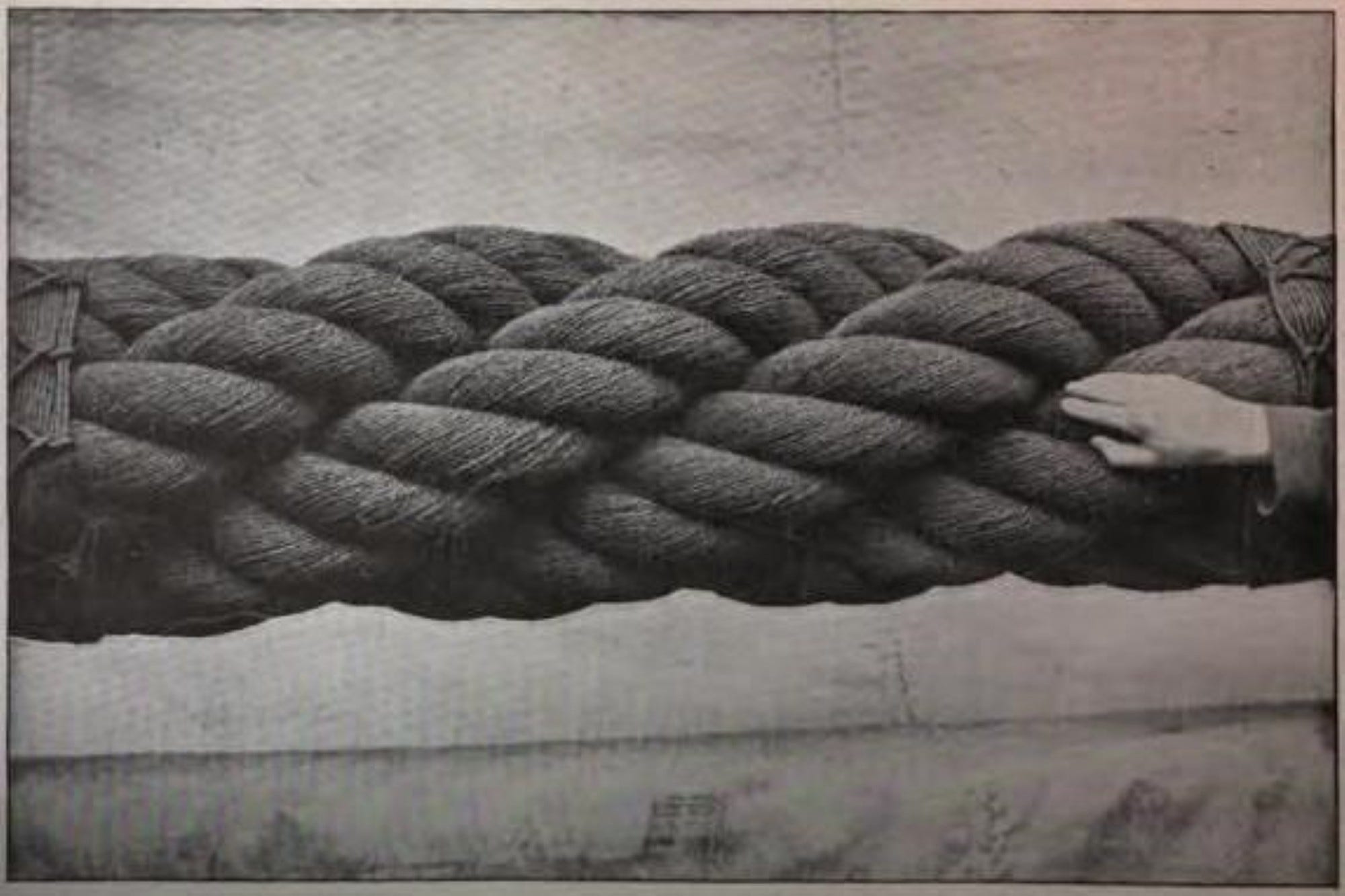

Over the years, this philosophy has crystallized into an image of history as a thickly woven rope, comprising billions of individual threads. Each thread represents an individual story line, but they’re so densely braided it’s impossible to label any specific era, or predict what’s coming next. The combinations aren’t random; some patterns seem to come up again and again, but the vast, tangled mass prevents easy characterization.

For us, this rope metaphor provides a better sense of perspective. Take that thick black global pandemic strand. It’s just re-appeared for the first time in over a century, but should disappear again fairly quickly. Scarily, the glowing red filaments of climate change are starting to show up everywhere, and expanding all the time. They’re hopelessly snarled up in a tangle of extractive capitalism, technological innovation, ecological collapse and regenerative practices, and nobody really knows how that’s all going to play out.

The colonialism and slavery strands are mostly gone, thank god, but the racism and sexism ones are proving much harder to get rid of, and the blood-soaked strings of war, while far less common than they used to be, seem unlikely to ever disappear. The bright blue cords of democracy are fraying around the edges, which is worrying but then again, it’s not the first time that’s happened. On the upside the grey strands of poverty are far less prominent than they have been at any other time in our past, although still far too prevalent, while the sickly white threads of preventable childhood disease are gradually tapering out.

This is the story of humanity, not as narrative, but as a shared, evolving experience. Like Vonnegut’s story arcs, it’s an idea that should be held lightly, and used only as a starting point. We prefer it though, because it gives us hope. Not the hope of a new dawn and not the hope of sitting back expecting the gears of history to grind on towards prosperity, but hope for something much better; something that we are all a part of and that we each have a responsibility to work for, and hard.

Ultimately, there’s no way of judging whether we’re living through Collapse or Renewal. Future generations will decide that for us. The only thing that matters is the part we play. We can choose which strand of the rope we belong to. We can add to its grand weave, in the way we treat other people, in the daily work we do, in the decisions we make about where to put our energy, in the leaders we vote for and in the words that come out of our mouths.

And if, in the end, our worst fears come true, and we find ourselves in the last days, standing on the mountaintops, watching the waters rush in and the flames licking at the walls, whose company would we rather be in? The cynics insisting “we told you so?” Or the people saying “You know what? We gave it everything we had.” We know our answer. We’ll be here, telling stories of Renewal, come what may.

Here’s Jane Goodall again.

What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.