The Telemetry

All the news the headlines missed in 2025.

What terror doth it strike into the mind

To think of One, who cannot see, advancing

Towards some precipice's airy brink!

But, timely warned, He would have stayed his steps;

Protected, say enlightened, by his ear.

William Wordsworth, The Excursion VII (1815)

Chlamydia trachomatis is a bacterium, about a quarter of a micrometer across, small enough that half a million can fit on the tip of a sewing needle. It’s a shape-shifter: one strain causes chlamydia, the world’s most common sexually transmitted infection. Another strain targets human eyes, causing a disease called trachoma, and trachoma is a lesson in how much damage time can do.

It begins in young children, spread by flies attracted to the moisture in their eyes and noses. At first it feels like conjunctivitis. The kids rub constantly, their eyes glued shut in the mornings from discharge, spreading the infection to their siblings. This goes on for years, infection after infection, each one leaving a little more scar tissue.

Then comes the turning point, quite literally. The scarred eyelid turns in on itself. At first, one or two lashes touch the eye. They can be plucked, but grow back in weeks, thicker. More turn inward until blinking becomes an assault. Sunlight is agony. Squinting presses the lashes down harder. The pain is relentless; people describe it as glass shards scraping the cornea. Sleep becomes impossible because closing your eyes hurts too much.

Trachoma is old. Evidence of it has been found in human skulls from the Ice Age. The Ebers Papyrus, written two centuries before Tutankhamun, contains a suggested treatment: after ripping out your eyelashes, apply an ointment of myrrh, lizard blood, and bats’ blood. Thousands of years later, homemade remedies aren’t much better, so people employ increasingly desperate coping strategies.

They tie string around their eyelashes, pulling them away from the eyeballs. When the pain becomes unbearable, they pluck the lashes out - with tweezers if they have them, with fingernails if they don’t. Some burn their lashes away with hot ash. In the worst cases, they cut notches in their eyelids to change the angle. Left untreated, the cornea scars until vision disappears entirely, but the lashes keep scraping even after the world goes dark.

In the 19th century, trachoma was endemic in Europe and North America. Charles Dickens based Nicholas Nickleby on a boarding school in Yorkshire where the boys were blinded by what was then known as Egyptian ophthalmia. William Wordsworth suffered repeated infections that left him fearing blindness, which he recorded in The Excursion. Irish immigrants were examined at Ellis Island and deported if infected. It ravaged Native American communities and the barracks of the First World War.

By the mid-20th century though, trachoma had vanished from the West, not because of medicine, but as a side effect of prosperity. Indoor plumbing meant faces could be washed with clean water. Sewage systems and garbage collection eliminated the flies. The disease retreated to the world’s poorest places, where it persists today, the most common infectious cause of blindness on the planet, a plague that’s been with us since before the pyramids.

Or at least it was. In November 2025, Egypt eliminated trachoma. Senegal, Burundi, Mauritania, Fiji, Togo and Papua New Guinea eliminated it this year too, while India, Pakistan and Vietnam crossed the finish line in 2024. A decade ago 192 million people lived in areas where trachoma was endemic. That number has now almost halved, and the number of people blinded has fallen from 3.5 million to 1.2 million.

It’s one of the most inspiring things I’ve ever heard of, one of best things happening in the world right now, yet not a single major news organisation reported anything about trachoma in 2025.

When something goes wrong in space, the public watches the visual feed: explosions, debris, visceral evidence of danger. Mission control watches everything else: oxygen levels, trajectory drift, the systems that determine whether the crisis is survivable. This year felt like being stuck in that room. On the screen, collapse: 56 conflicts raged, the most since the Second World War. Gaza remained a graveyard, satellite imagery showed blood in the rivers of Sudan, and Putin’s invasion of Ukraine approached its fourth anniversary.

According to Reuters four in ten people now avoid the news, and after a year like this, who can blame them? What made 2025 exceptional wasn’t any individual atrocity but their sheer velocity, the sense that they arrived bullet-like, leaving no room to recover. Wildfires in Los Angeles, Zelensky’s humiliation in the White House, a Swiss village buried by mud and ice, antisemitic terror attacks in Manchester and Sydney. It was the year the predators stopped pretending. Nations slashed aid and started stockpiling missiles. The rich got tax breaks and stock market highs, everyone else got expensive eggs and crippling mortgages.

Beneath this ran a deeper anxiety: that digital technology has done permanent damage, replacing our shared stories with fragments of conspiracy and grievance. Oxford’s word of the year in 2024 was “brain rot.” This year, it was “rage bait.” And while we scrolled, the coral reefs bleached. Glaciers lost ice at record rates. Bulldozers kept flattening forests. Ships kept bottom-trawling. In Texas, the Guadalupe River rose overnight and drowned children in their beds. The planet is on track for temperatures that will reshape continents, yet the political will to change course, incredibly, went backward.

I watched it all, spending hundreds of hours mainlining all the corruption and cruelty until the scale stopped registering. I can’t remember ever feeling more angry. But each week, I also monitored the consoles at the back of the room: WHO technical reports, Spanish-language newspapers, Chinese state media, energy analysts on LinkedIn, a website devoted to a guru of transcendental meditation that publishes good news because “the media is a mirror of collective consciousness.”

We published 38 editions of our newsletter this year, featuring 1,932 stories from 170 countries, and what we found was that while the headlines kept insisting on collapse, the data - child mortality rates, vaccination coverage, emissions intensity, deforestation curves - kept showing stubborn progress. While everyone was staring in horror at the flames outside the capsule, we were looking at telemetry that said there was more than enough oxygen to make it home.

This gap, between the world as it is and how we’re told to see it, comes down to a choice about what we do with our attention. Mission control doesn’t ignore danger. It’s acknowledged, monitored, taken seriously. But knowing which emergencies require immediate action means you need to watch all the instruments, not just the alarms. That’s the difference between panic and an effective response.

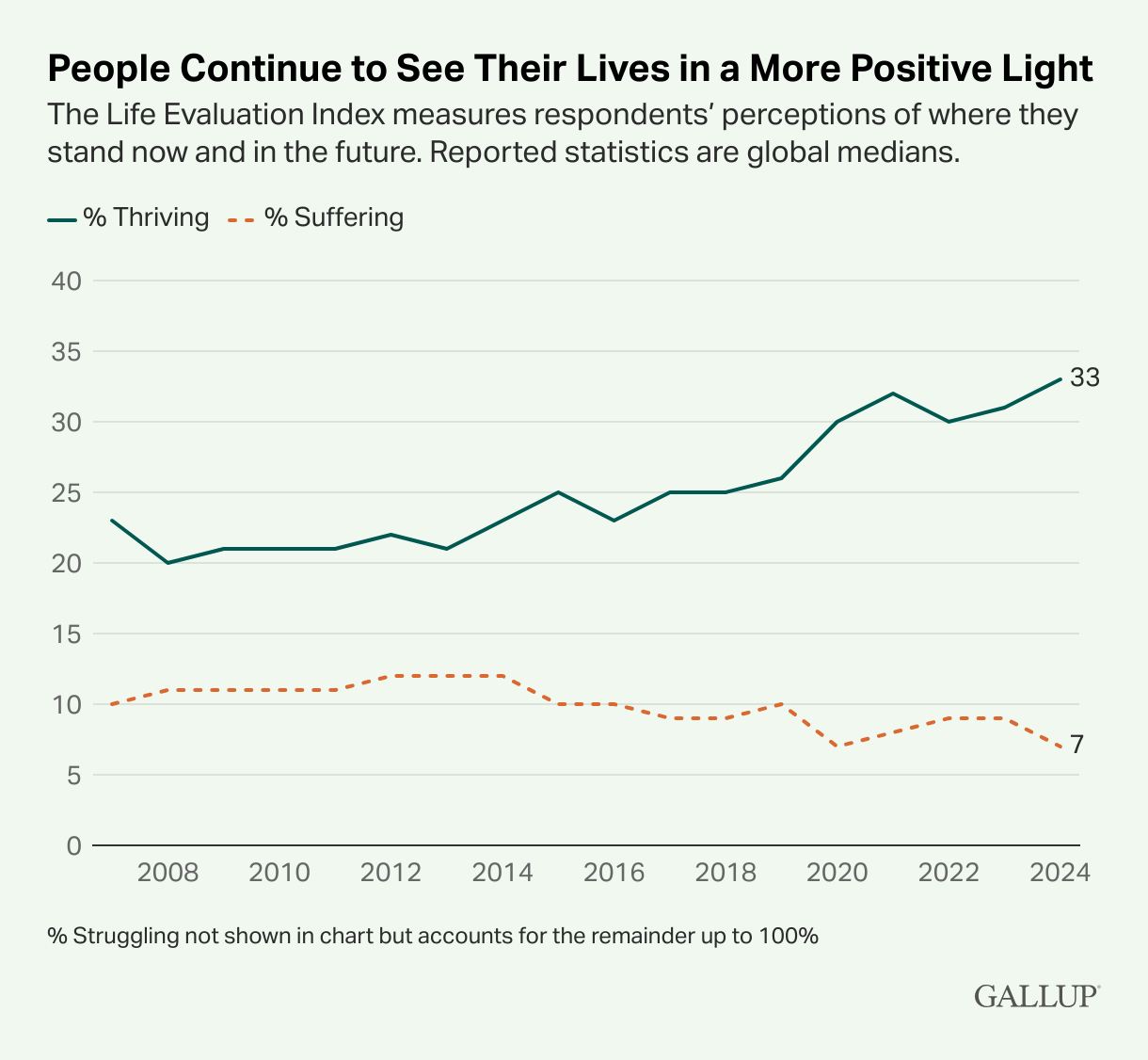

Every year, Gallup surveys around 1,000 people each in 142 countries, asking about their lives and expectations. In its most recent edition, 33 percent of respondents said they were thriving, the highest proportion on record. The share who said they were suffering dropped to 7 percent, matching the lowest level since tracking began in 2007. A decade ago it was 12 percent.

You might expect these numbers to feature prominently in coverage about the state of the world. They don’t. A record four in five people are satisfied with their personal freedoms and three in four say their country is a good place for children to learn and grow. Economic optimism has rebounded to its highest point since the financial crisis. More people in more countries report living better lives than at any point since measurements began.

If you watched the news, you'd think these people were delusional. Everyone knows the global economy has had a terrible year. In April, Trump's tariffs triggered a sharp rise in trade tensions. Growth projections fell by 0.4 percentage points. But by November, they’d recovered to exactly where they started: 2.7 percent. The pattern has become familiar. Since the pandemic, global growth has repeatedly exceeded expectations.

But resilience isn’t evenly distributed, and neither is the attention. While American and British media spent a lot of this year focusing on sinister political forces and affordability crises, in much of the rest of the world people felt measurably better about their prospects. Not because growth was spectacular (it wasn't) but because daily life kept improving in ways that GDP doesn't capture.

Consider what happened with food. Global hunger is falling for the first time since the pandemic, driven by gains in Asia and the Americas. In 2025 the world produced record harvests of wheat, rice and soybeans for the third consecutive year, pushing grain prices down 8 percent and rice prices to their lowest in 18 years (and this required less land - global farmland peaked in the 2000s and has been falling ever since, according to the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization).

That abundance has translated into extraordinary gains in places you don’t often hear about. Indonesia reduced childhood stunting from 30.8 percent in 2018 to 19.8 percent in 2024, one of the largest and fastest drops ever recorded, and in 2025, it reached 30 million more women and children with free meals. This was part of a global surge: over half a billion children were fed at school this year, 100 million more than were fed in 2020.

Global unemployment reached its lowest level since 1991. More than 80 percent of the world's adults now have access to bank accounts, up from half in 2011. Extreme poverty remained stubbornly high in conflict-affected and fragile states but is falling almost everywhere else. Not just India and China but Indonesia, Mexico, Uzbekistan, Nepal, Vietnam - countries where hundreds of millions have escaped the worst kinds of deprivation in recent years. None of this resolves affordability crises in the rich world. But it complicates the narrative that everything everywhere is getting worse.

The gains extended beyond food and income. In August, the WHO and UNICEF released data showing that over the last decade 961 million people gained access to safe drinking water, 1.2 billion gained safe sanitation, and 1.5 billion gained basic hygiene services. Over the same period the number of people without electricity fell by 292 million, even as the global population grew by 760 million. According to the International Energy Agency, this represents the fastest expansion of electricity access in history.

The scale of this achievement is staggering. Charles C. Mann describes them as ‘secular cathedrals’: electric grids, public water, food supply chains and public health networks that rank among civilisation’s greatest accomplishments. These systems change lives in the most tangible of ways. Homes that now have power and toilets. Clinics with soap and handwashing basins. Hundreds of millions of women who no longer have to carry water each day. Countless communities that can focus on more than just survival.

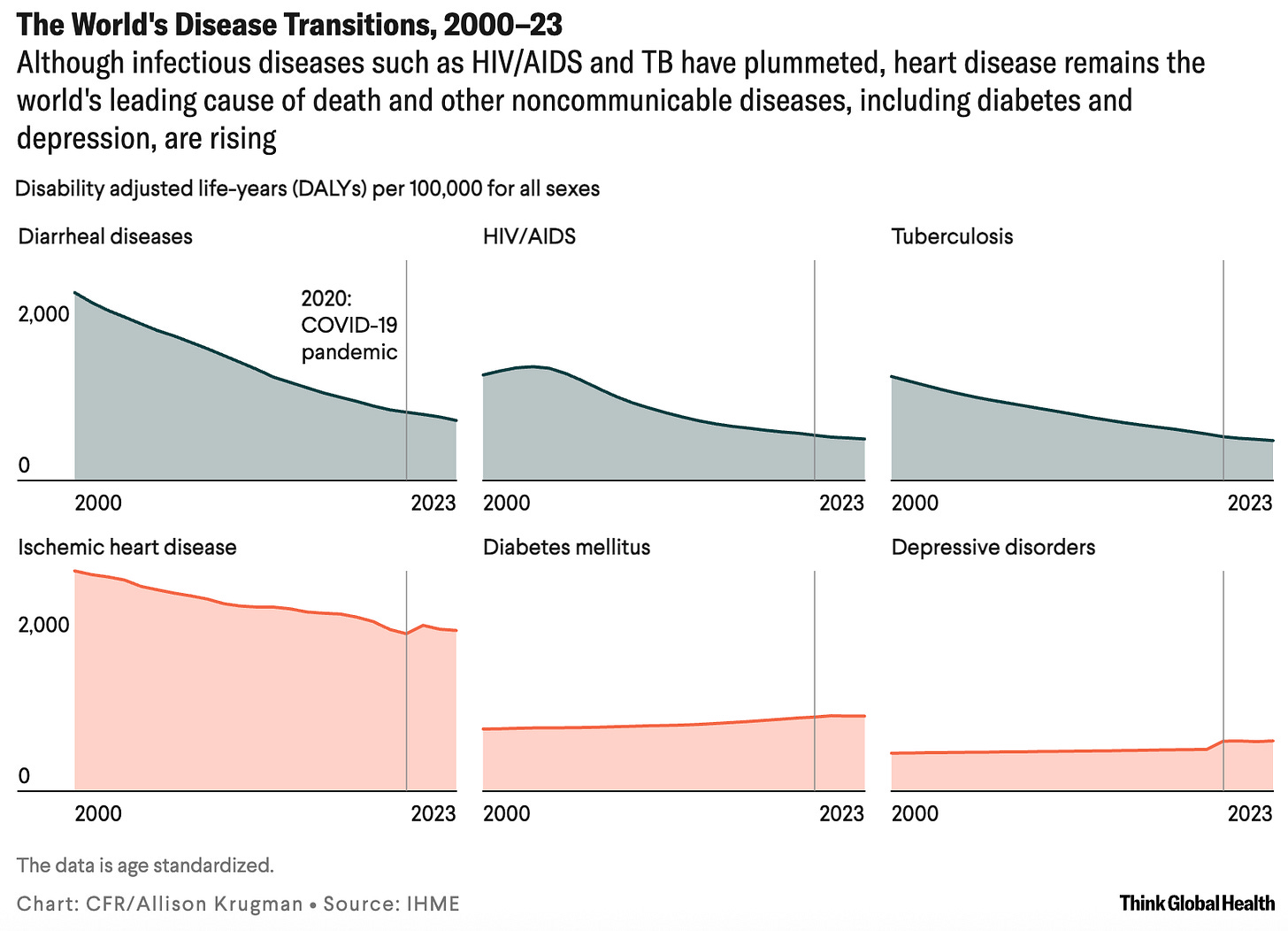

Yet even that wasn’t the best thing we saw in the telemetry this year. In September, The Lancet released a report with one of the most extraordinary statistics I’ve ever seen: since 2010, humanity’s total burden of illness and early death has dropped by 12.6 percent, driven by declining deaths from the world's deadliest infectious diseases: tuberculosis, lower respiratory infections, diarrhoea, HIV/AIDS, all down by between 25 and 49 percent.

This progress has been so dramatic that for the first time in our species' history, lifestyle diseases (heart disease, cancer, diabetes) have displaced infectious illness as the dominant global threat. And here, mortality is falling too. The probability of dying from one of these diseases before 80 has declined in four out of five countries since 2010. Global cancer death rates are roughly a third lower than their early-1990s peak - child leukaemia deaths are down 59 percent. In the United States, every generation now has lower dementia risk than the last.

A record 17 countries eradicated a disease this year, the highest number in history. It wasn’t just trachoma; Niger became the first African nation to eliminate river blindness, Guinea and Kenya beat sleeping sickness, the Maldives achieved the world’s first triple elimination: no babies born with HIV, hepatitis B or syphilis. Japan and 21 Pacific nations were declared free of measles and rubella this year too.

More than ten million children were vaccinated against malaria, part of a broader surge that pushed global vaccination levels to record highs. Not because of belief in a moral arc, but because thousands of people worked together across continents: scientists in labs in England and India, healthcare workers loading cooler boxes onto bicycles, market women passing messages between vegetable stalls, religious leaders finding Quranic verses to counter vaccine myths.

Perhaps more striking still, the world is a safer place than ever before. Most people would dispute this; surveys show majorities in almost every country believe violence is rising. Yet the World Bank released data in September showing the global murder rate has declined on every continent during this century, and Gallup found that 73 percent of people globally now feel safe walking alone at night, the highest level ever recorded.

In 2025 the United States will almost certainly record its lowest murder rate in history. Not since the pandemic, not since the 1990s crime wave, but lower than any year since the FBI began tracking in 1960. Violent crime is at its lowest level since 1968. Property crime is at the lowest rate ever measured. Baltimore, which The Wire made synonymous with drug violence, has seen emergency rooms that once overflowed with gunshot victims nearly empty out.

Even on the world’s most dangerous continent, homicide rates have declined in the last decade, by 22.6 percent in South America and 58 percent in Central America. Brazil's homicide rate fell 15 percent in the first half of 2025, reaching its lowest level since 2012. Mexico's daily murders have dropped by 37 percent under President Sheinbaum. Jamaica recorded a 42 percent decline, the steepest annual fall in four decades.

We have built the safest civilisation in human history while convincing ourselves that we live in the most dangerous. Billions of people experienced measurable improvements in health, safety, and material conditions in 2025. That progress didn’t make the news. But it happened anyway, one vaccine, one school meal, one kilowatt-hour at a time.

Look, I don’t want to sound like some bloodless bureaucrat here. You can’t fact-check people out of a feeling. For hundreds of millions, the world feels like a terrible place at the moment. If you’re a democracy activist languishing in a Hong Kong jail or a single mother in New Jersey struggling to pay the rent or a cobalt miner risking your life in the DRC, lines on a graph don’t matter.

That said, I do think the collapse merchants have gotten carried away. We now have an entire genre about living in the worst timeline, about how fascism is inevitable and the kids are doomed, and almost all of it is created by people cosplaying the apocalypse from positions of extraordinary comfort. They’re being lazy. It's easier to predict the end of the world than to wrestle with the truth, which is that some things are genuinely scary, some things are going great, and most of it is just really complicated.

But nuance doesn’t sell. Pessimism does. It sounds smart, sophisticated, proof that you’re a clear-eyed realist. Plus, doom is dramatically satisfying in ways that incremental progress never can be. You get to use words like predator, crippling and conspiracy. You get to be the prophet who saw it coming, brave enough to tell hard truths while collecting your advance and planning your next speaking tour.

The problem compounds when 90 percent of the world’s English-language media comes from the United States. What reads as analysis of global collapse is mostly American psychodrama mistaken for planetary diagnosis. The Republic of Letters has been annexed by the Republic of Feelings, and the feelings in question belong to people whose material circumstances remain comfortable enough to afford the luxury of existential dread.

No story in 2025 showed this more clearly than the assassination of Charlie Kirk. For weeks, this dominated news cycles, social media feeds, conversations. It made headlines in hundreds of countries and ended the year as Wikipedia’s second most-read article, behind only the death of Pope Francis in April. Humanity devoted billions of hours of our attention to this over the course of September and October 2025.

The coverage was almost entirely worthless. Instead of investigations into political violence or security failures, we got endless cycles of hypocrisy-identification. People argued over whether to feel sympathy. The assassin’s online history got picked over for tribal markers. Antifa or groyper? Weeks of takes that resolved nothing, a drizzle of commentary that amounted to ‘mimetic outrage spirals’ (thanks Sam Kriss) masquerading as incisive political discourse.

During the weeks that this story dominated our feeds, the UN High Seas Treaty was ratified, giving governments power to establish conservation zones across the two-thirds of ocean that lie beyond national borders. NASA announced that Perseverance had found mudstone covered in markings resembling those left by microbes on Earth, the strongest evidence yet that life once existed on Mars. The World Bank released a report showing nearly 100 million children have been lifted from poverty in the last decade.

Bolivia became the 14th Latin American country to ban child marriage, following a four-year campaign led by girls and civil society groups. In Japan, new figures showed same-sex partnerships are now approved by 92 percent of municipalities. Pakistan launched its first vaccination drive against cervical cancer, mobilising 50,000 healthcare workers. A Dutch-American team successfully treated Huntington’s disease for the first time. Philanthropists in New York announced deals to supply a new miracle HIV drug to 120 low and middle-income countries.

Solar became the largest source of electricity in California, overtaking fossil gas for the first time. Peru created a massive protected area of rainforest that will lock away over half the country’s carbon. Mexico reported that wild jaguar populations are up 30 percent since 2010. Brazil, the fourth-largest cosmetics market in the world, banned animal testing. In the Pacific, chiefs from Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu endorsed a proposal for the world’s largest ocean reserve, an area the size of the Amazon rainforest.

We didn’t hear any of these stories though, because we were too busy scrolling through hot takes about Erica Kirk, Jimmy Kimmel, and free speech. According to the logic of our modern information apparatus, one of the most important things that happened in 2025 was the death of an American political entrepreneur, an event deemed a thousand times more newsworthy than a treaty to protect two-thirds of the world’s oceans, tens of millions of children escaping poverty, and the potential discovery of extraterrestrial life.

The news is not the report. It’s what Jennifer Mercica calls ‘a misery machine’, specialising in stories with very specific rules about what matters. Those rules have nothing to do with importance and everything to do with what makes compelling narrative. Engraved memes on bullet casings, drone strikes in Ukraine, masked agents dragging people off streets - they all offer what the machinery requires: visceral imagery, immediate threat, endless angles for outrage.

A story about Morocco becoming the 60th nation to ratify a global maritime treaty, thereby triggering its entry into force? That doesn’t tick any of the boxes. Neither do disease elimination or electricity access. These things happen slowly, invisibly, the result of decades of incremental gains. Cathedral-building, not crisis. There are no villains, no victims, no dramatic turning points. They reduce threats rather than amplify them, make the world safer rather than more dangerous. From an attention-economy perspective, that makes them worthless.

This is why 2025 looked so awful. Not because journalists were lying but because the entire media apparatus is structured toward grievance-based attention farming. Progress remains invisible because it doesn’t generate the emotional payload required to compete. What remains is a funhouse mirror: accurate in its particulars, grotesque in its proportions. The fires were real. The floods killed people. The predators did stop pretending. But staring at the feed while ignoring the telemetry creates panic, and panic is what creates space for populists who insist they alone can fix the disasters we're told define our age.

By this point, I know the climate activists will be climbing the walls. Health, sanitation, education, nutrition, safety. Fine. But there’s no progress on a dead planet. What's the point of eliminating trachoma when rising temperatures spread new diseases? Who cares about electricity access when crops fail and the sea swamps our cities? All this runs on a devil's bargain: we’re still pumping out more carbon.

Except we aren’t. Since the Paris Agreement entered into force in 2016, China has been responsible for roughly 90 percent of global emissions growth. Strip China out and emissions from the rest of the world have flatlined in the last decade. In other words, it worked! All the pleas, the backroom deals, the documentaries, the marches. But while those battles raged, China exploded, pumping out hundreds of millions of extra tonnes of carbon each year, the equivalent of adding five Germanys to the global emissions ledger.

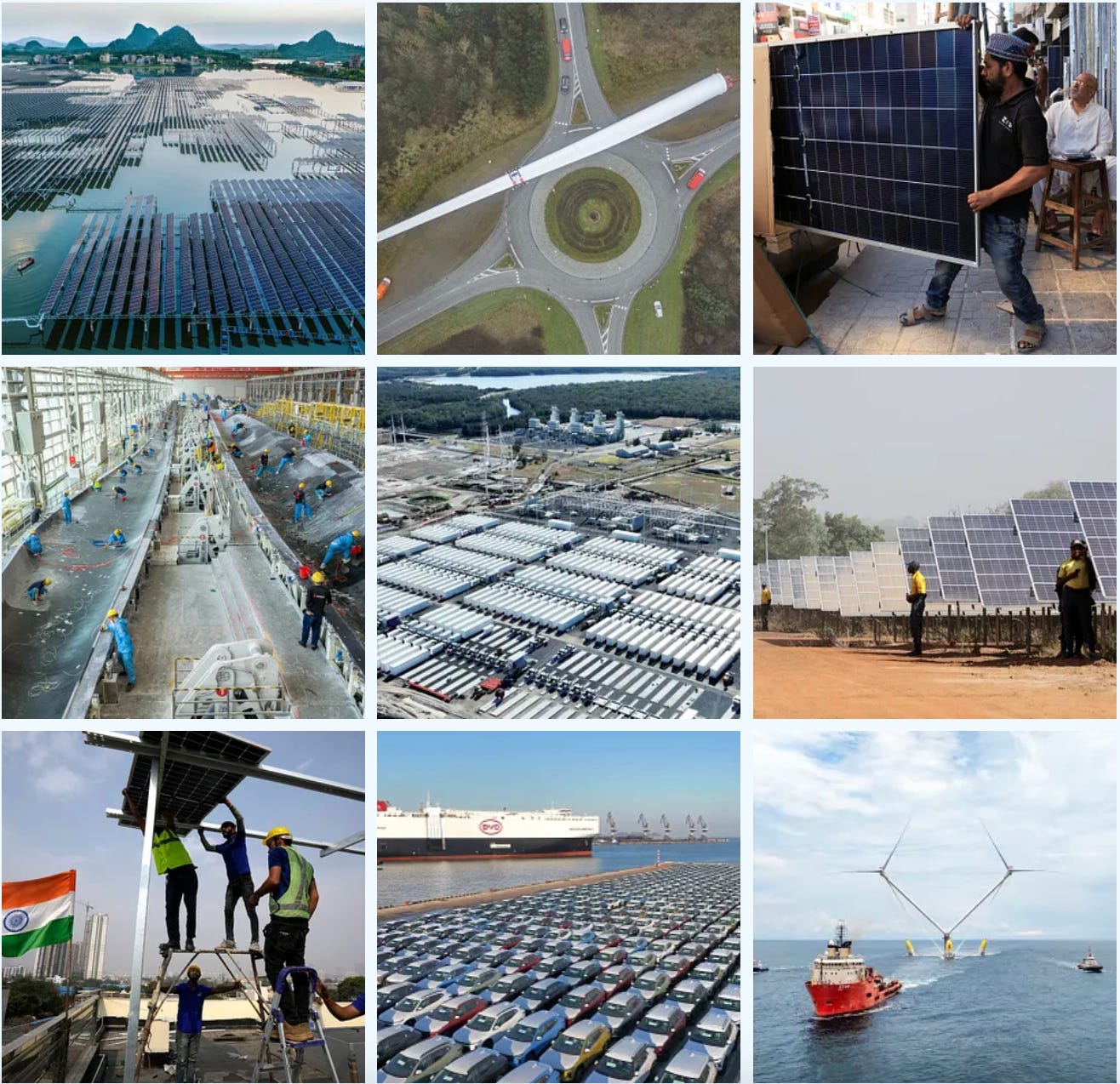

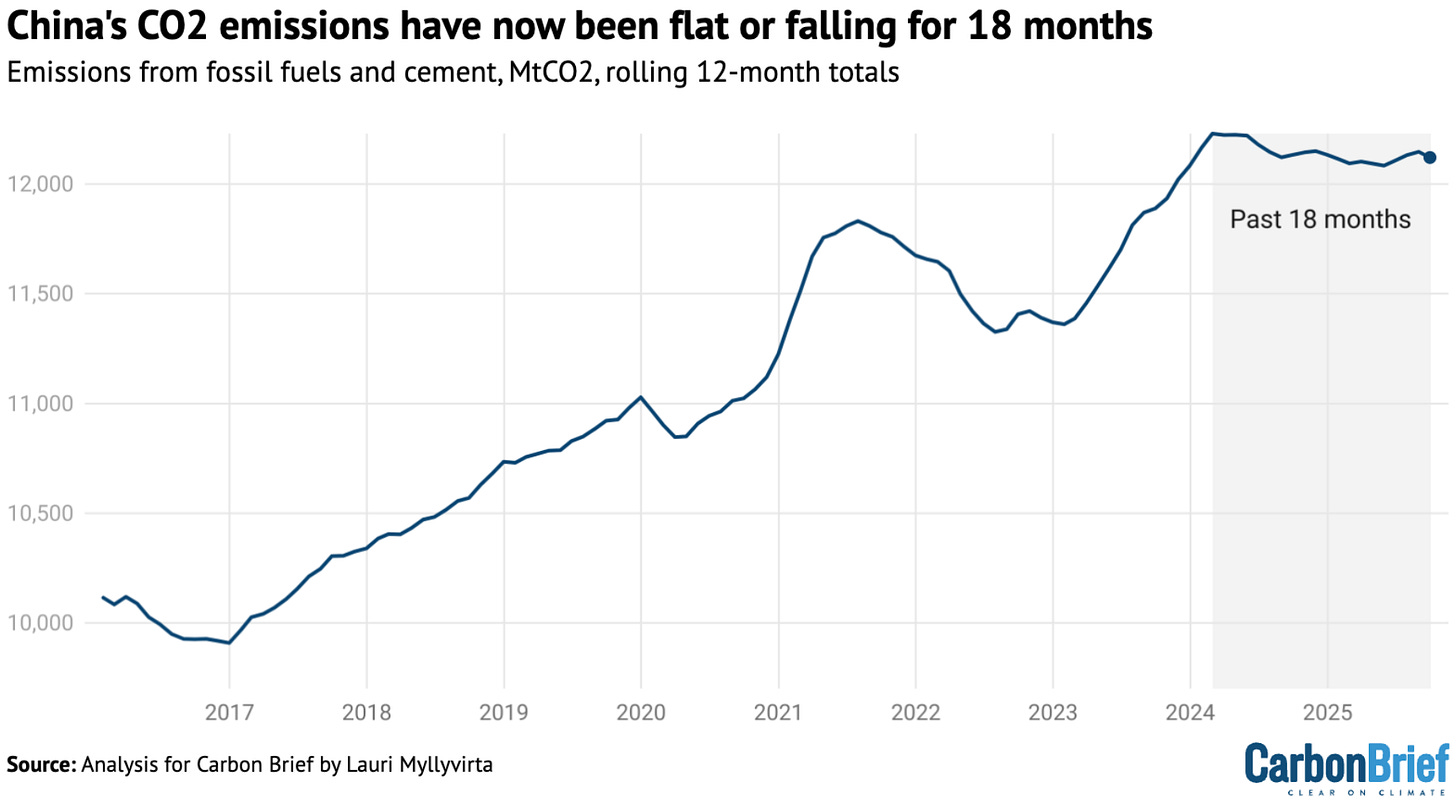

Now that’s changed. China’s emissions have been flat or falling for 18 months. Unless there’s a dramatic last minute revision, China’s carbon emissions will fall over the full calendar year, not because of an economic downturn, but because the structure of its energy system is transforming. This is the biggest turning point in the history of energy. The country responsible for a third of global emissions, the one adding two United Kingdoms’ worth of electricity demand every year, is now satisfying all that growth with panels, turbines and batteries instead of coal or gas.

The scale of the buildout is staggering. China is expected to add at least 330 gigawatts of solar and wind capacity this year. To give a sense of scale, in May alone, it installed 230 million solar panels, roughly the same amount in a month that Germany has installed in its entire history. In November, electric vehicle production hit 52 percent of all vehicles while production of internal combustion vehicles fell 10 percent. Solar generation grew 50 percent year-on-year, wind by 37 percent. Coal’s share of total electricity dropped to 53 percent, down from 59 percent just two years ago.

More importantly, China is exporting its clean energy transition everywhere. It manufactures over 70 percent of the world's solar panels, wind turbines and batteries, at a scale that has crashed prices and made clean energy the obvious economic choice. Pakistan generated a third of its electricity from solar in 2025, up from zero six years ago. Solar panel imports to Africa rose by 60 percent. In Australia, renewables just overtook coal. India’s power sector emissions fell for only the second time in half a century. The United Kingdom now generates more than half its power from wind and solar.

For the first time in history, renewables overtook coal this year as the largest source of global electricity, with wind and solar covering all growth in the first half of the year. That’s why Science called renewable energy the breakthrough of the year. It’s the structural change we’ve all been waiting for. Not pledges at climate summits, but the moment when clean energy grows fast enough to meet rising demand and begins displacing fossil fuels. Three of the world’s four largest emitters - China, the EU and India - are now seeing fossil generation flatten or fall.

Even in the United States, where the Trump administration spent the year trying to reopen coal plants and block wind farms, 92 percent of new electricity capacity through November came from solar, wind and batteries. Despite the president’s repeated insistence that windmills are national security threats and too expensive to operate, wind accounted for more new gigawatts this year than fossil gas. The commercially viable version of reality kept asserting itself regardless of what was said on Truth Social.

Ultimately, this year settled an argument that dominated climate discourse for months: energy transition or energy addition? Are renewables displacing fossil fuels or just getting stacked on top? China’s declining emissions provided the answer. Renewables are replacing coal and gas, not supplementing them. Of course, climate isn’t just electricity. It’s transport, food systems, land use, industrial heat, a complex equation with dozens of variables. But ten years ago, projections showed us heading toward 4°C or more of warming. Today those estimates sit at 2.7°C.

That’s not good enough. We’re going to blow past 1.5°C, and the loss of the reefs, precious ecosystems and coastlines will be among humanity’s greatest crimes. But we’re still on a better path than we were. If current patterns hold, we might stay below 2°C, which is the difference between catastrophic and survivable. The oil and gas companies may have captured politics: Trump in the White House, climate action blocked at COP, petrostates emboldened. But the decisive shift is happening in Shandong province and the Atacama Desert and on suburban rooftops in Karachi. That was the climate story of the year. Everything else was an afterthought.

In October, Rhett Butler, founder of Mongabay, published an essay that circulated widely in my corner of the internet. “Optimism, properly understood, is not a mood,” he wrote. “It is a method.” His argument was simple: treat optimism as a discipline. Tell stories that build agency. Refuse the lazy fatalism that mistakes headlines for trend lines. Destiny is not fixed.

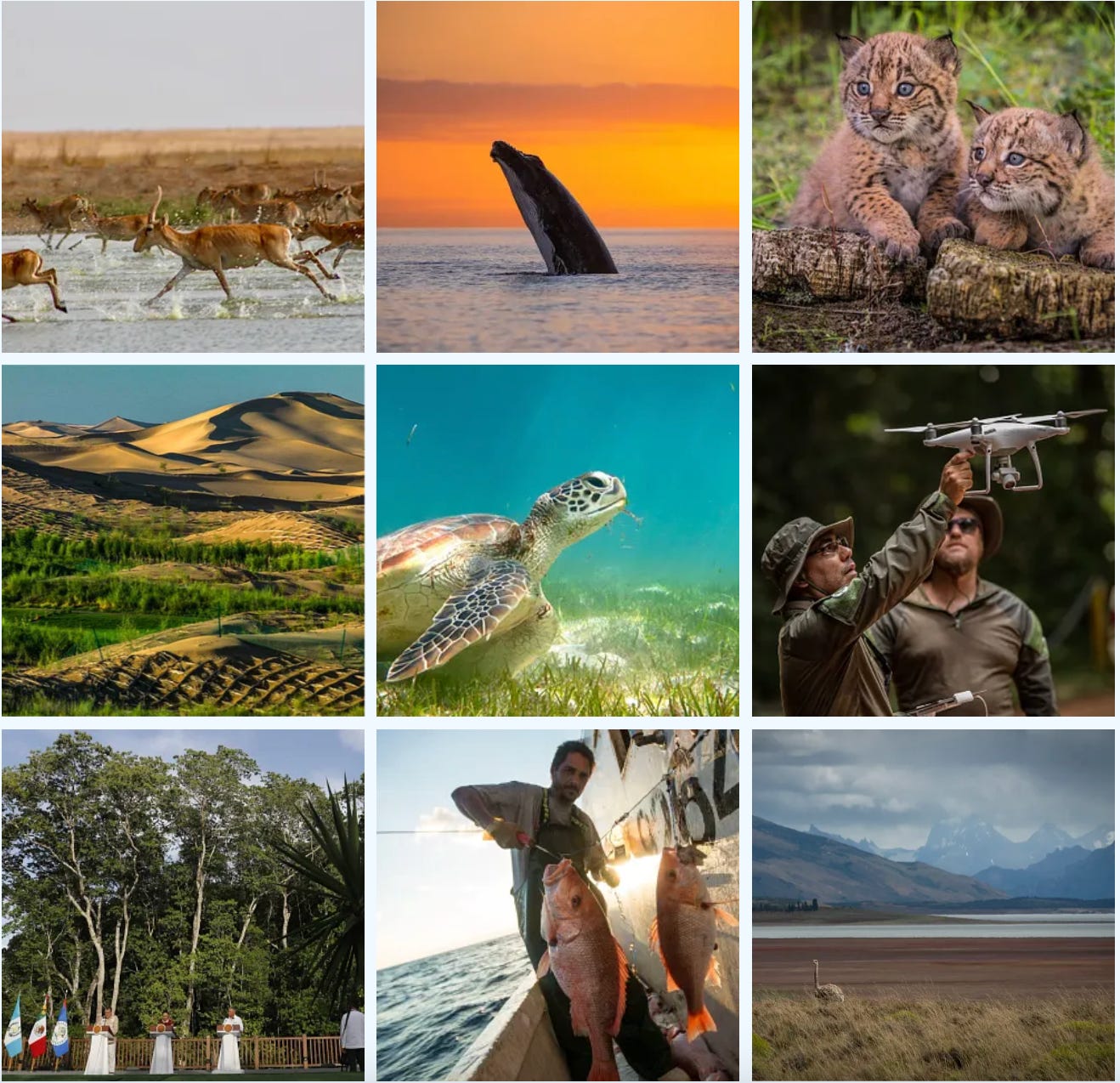

That method matters because narratives, once established, are difficult to dislodge. The Sixth Mass Extinction for example, has become shorthand for the biodiversity crisis, repeated so often it feels like settled fact. But in November this year, Kristen Saban and John Wiens, two ecologists from the University of Arizona, published research that complicates the story. After analysing 912 extinctions across plants and animals over the past 500 years they found that extinction rates peaked about a century ago and have been declining since.

Their findings don’t deny an environmental crisis. Most historical extinctions were driven by invasive species on islands: rats, pigs, and goats wiping out birds, plants, and reptiles with no defences. Today’s threats are different: habitat loss, climate stress, ecosystem degradation. On multiple fronts this year though, people went after those threats, and what they pulled off was remarkable.

Consider the saiga antelope. In 2006, roughly 30,000 remained scattered across the grasslands of Central Asia. The animal had survived ice ages, but industrial hunting, habitat loss and a series of catastrophic die-offs from bacterial infection had pushed it close to extinction. What followed was not glamorous: anti-poaching patrols across Kazakhstan and Mongolia, cross-border coordination between governments that never agree on anything, better law enforcement against horn trafficking.

By 2025, the population had climbed to nearly four million.

The saiga wasn’t alone. This year we learned that India’s tiger population has doubled in a decade. Iberian lynx went from 100 at the turn of the century to over 2,400. Green turtles were removed from the endangered list. Humpback whales in eastern Australia now exceed pre-whaling numbers. In New Guinea, Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna, feared extinct, turned up on camera traps. European bison have risen from 54 in the 1920s to 10,000 today. Black rhino numbers in Africa are recovering.

None of these stories made headlines. The recoveries accumulated quietly. The work was technical, expensive, and slow. Transmitters on every animal. Artificial insemination. Predator-free zones. Habitat corridors maintained across borders. Communities paid to monitor instead of poach. That stuff just can’t compete with the latest drama from Washington DC or speculation about whether Ariana Grande is on Ozempic. The machinery has rules, and gradual success doesn’t qualify.

But it works. Penny Langhammer and colleagues reviewed 665 conservation interventions and found that two-thirds either improved biodiversity or slowed its decline. Habitat protection works. Invasive species removal works. Restoration works when maintained over time. Where interventions failed for their intended targets, other species often benefited unintentionally, or the failures informed better strategies elsewhere. Success wasn’t guaranteed, but it wasn’t rare either.

Forests told a more complicated story. On the upside, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization reported that net forest loss has fallen by more than half since the 1990s, from 10.7 million hectares per year to 4.12 million. Millions of hectares of tropical forest are now in some stage of natural regrowth, but that’s because destruction continues. Forests regenerate after being cleared, burned, or logged. Each flare-up opens space for new shoots, even as it drains the ecosystem’s ability to recover.

Still, progress was real. In Brazil, deforestation in the Amazon fell to its lowest level in 11 years. Colombia declared all its rainforests, an area the size of California, off-limits to new large-scale extraction. Across the broader region, a patchwork of around 20,500 square kilometres of forests, wetlands, cloud forests, and páramos were protected, placing long-term stewardship in the hands of Indigenous peoples and local governments. Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize launched a tri-national reserve protecting 57,000 square kilometres of Maya forest, the largest protected area in the Americas after the Amazon.

Rewilding accelerated. Roughly 18 million square kilometers have been spared from cultivation since the early 2000s. That abandoned land is reverting to grasslands and forests across Europe, North America, Australia, and Central Asia. As people abandon those spaces, wildlife has returned. Europe’s wolf populations have increased by 58 percent in a decade. Golden jackals surged 46 percent. Brown bears climbed 17 percent. In North America, pumas, black bears, and grizzlies have reclaimed millions of square kilometers.

Simple technologies bent outcomes too. China has converted tens of thousands of square kilometres of its deserts into green farmland, using a simple technique involving straw grids. In the last decade deaths from air pollution, the thing that kills more people than anything else, have dropped by 21 percent, driven largely by billions of people gaining access to cleaner stoves.

Animal welfare is another bright spot. A decade ago, fur farms killed 140 million animals a year. That number has now fallen to less than 20 million. The collapse came quicker than anyone expected: luxury brands abandoned fur after Gucci’s 2017 pledge, COVID-19 outbreaks on mink farms forced closures across Europe, and demand crashed in Russia and China. What was a $40 billion industry a decade ago had been gutted by a combination of consumer pressure, disease risk and regulatory tightening.

Perhaps more striking still, ocean protections illustrated that collective action at scale still works. It wasn’t just the High Seas Treaty. Nations agreed to ban bottom trawling on seamounts, and several countries put a moratorium on the practice altogether. French Polynesia created the world’s largest marine protected area, covering nearly five million square kilometres. Samoa protected 30 percent of its ocean territory. Spain, Greece, Portugal, Colombia, and Tanzania all designated new reserves. In the United States, new figures showed that overfishing has been almost entirely stopped in territorial waters, with 50 stocks rebuilt since 2000.

The challenges we face are daunting, and well-meaning volunteers won’t be enough. Today’s pressures - heat stress, drought, degradation, ecosystem failure - are slower and more diffuse, so addressing them is going to require sustained institutional capacity rather than targeted campaigns. Do we have a chance of pulling it off? In 2025, across multiple domains in conservation and restoration, the answer was yes.

Somewhere in Egypt this year, a community health worker visited a village to distribute antibiotics and teach face-washing. She’s been doing it for years. That’s how diseases really get eliminated, not through medical breakthroughs or political bargaining, but because people keep showing up.

When I first started doing this work a decade ago I was certain that if I gathered enough data, stacked enough evidence, I could convince people that the collapse narrative was wrong. But you can’t prove the world is getting better or worse - it’s too hard to see from our current vantage point. We lack perspective. Future generations will decide that for us. They’ll look back and render their verdict based on what we left them.

Then I thought maybe I could identify the bad guys. Expose the masterminds, show who’s manipulating our attention and why. That didn’t work either. Part of growing older is realising that nobody is actually in charge. There’s no villain, no evil genius in a boardroom deciding what gets reported and what doesn’t. The system isn’t run by anyone; it’s the result of billions of choices made over decades, editors chasing clicks, coders optimising for engagement, audiences rewarding outrage, reporters following incentives. It’s not malicious. It’s emergent.

Now I do this work - watch the instruments, scour the internet, squint to see through the news - as a tribute to the millions of people who make it happen. Activists who spent years fighting child marriage in Bolivia. Nurses who traveled for days to distribute vaccines in Pakistan. Rangers in Zimbabwe who ran anti-poaching patrols around the clock for rhinos. Forest monitors in the Amazon who prevented fires from spiraling.

Engineers in China who somehow installed 230 million solar panels in a month. The scientists who ran malaria vaccine trials for years. The teams on opposite sides of the world who blew up the dams on the Klamath and Yangtze so salmon and sturgeon could spawn again. Researchers who devoted their careers to proving that conservation works. Diplomats who negotiated the High Seas Treaty through years of setbacks.

Egypt didn’t eliminate trachoma because of some natural law of progress. People did that. Solar panels didn’t transform the global energy system because of magic. That happened because people made the right choices, then kept making them long enough for the results to compound. The United States didn’t cut murder rates to all-time lows because of historical inevitability. Police and violence interrupters and youth workers made that happen.

None of them are going to stop because of who’s in the White House or Downing Street next year. They’ll load the cooler boxes and pull on their high heels for another day in court. That’s what makes the difference. Not a belief in progress, but the understanding that fixing is always harder than destroying, and that’s why it’s worth doing. All these people kept the world working in 2025.

They’ll do it again in 2026.

I just subscribed because you are doing incredibly important work. Thank you! I am mentioning you to every single person who tries to corner me with doom and gloom from mainstream media.

Bravo. A beautiful essay. Another inspiring year of work. Thank you.